Bamboo: Nature’s forgotten solution for green industry

- March 12, 2019

- 0

Bamboo: Nature’s forgotten solution for green industry

Natural resources manager Hans Friederich writes how bamboo can help provide developing countries with low-carbon infrastructure.

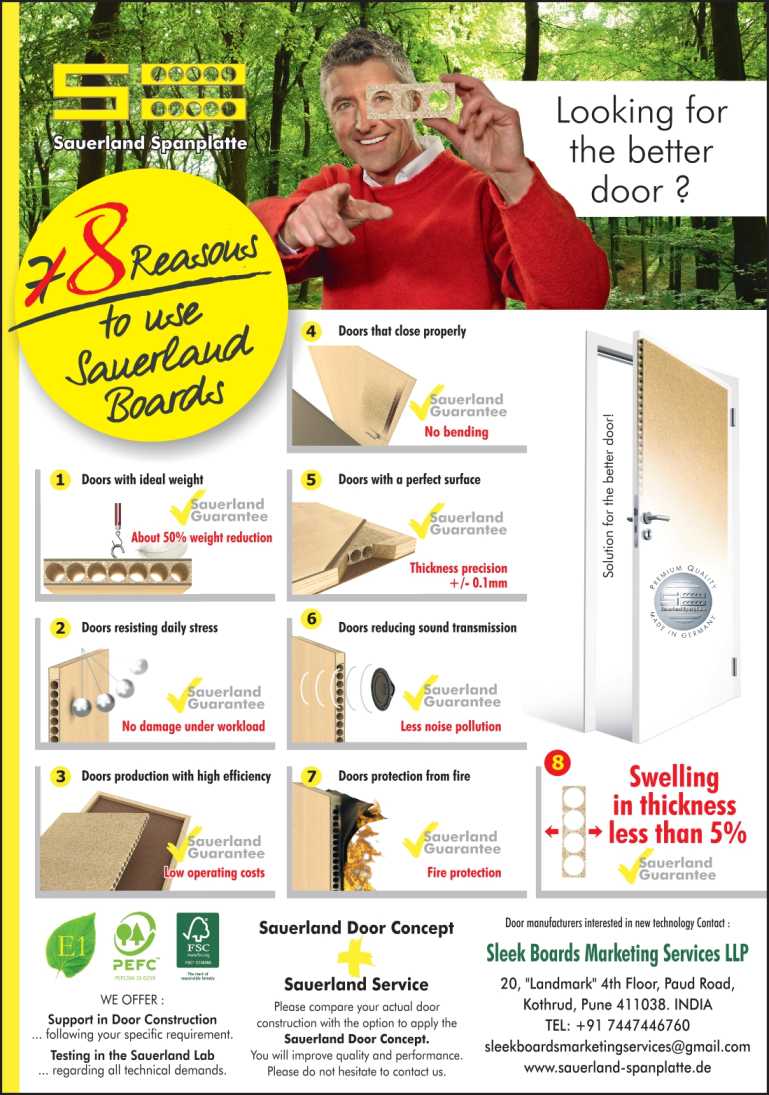

A construction worker on bamboo scaffolding in Xingpingzhen, Guangxi in China, where the bamboo industry is valued at US$30 billion. Image: Chris Goldberg

A construction worker on bamboo scaffolding in Xingpingzhen, Guangxi in China, where the bamboo industry is valued at US$30 billion. Image: Chris Goldberg

Sometimes, the best technology isn’t a technology at all. Bamboo, the fast-growing grass plant, common to Africa, Asia and South America, is a natural, renewable and low-carbon material with the tensile strength of steel, and a huge amount of potential for greening infrastructure.

As available, scaleable solutions go, bamboo is a forgotten solution. There are over 30 million hectares of bamboo across the world, and more is being planted every year: As a way to restore degraded land, and as a vital means of income for millions of people across the world.

The 44-member states who make up the International Bamboo and Rattan Organisation (INBAR) have national plans to restore an area of more than 5.5 million hectares of poor quality soil by 2020, using bamboo. When other countries in the world are taken into account, the figure may be much higher.

There is more research every year to support the vast potential of bamboo as a carbon sink. Like all plants, bamboo stores carbon. However, because it grows particularly fast—some species grow up to 90cm a day—and matures within a few years, it can be harvested regularly.

This means bamboo can create a large number of durable products which store carbon over several years, in addition to the carbon stored in the plant itself.

Recent research shows that over a period of 30 years, one hectare of bamboo plants and products can sequester up to 600 tonnes carbon—more than certain species of tree.

Replacing traditional materials with bamboo could be an important way to ‘green’ emissions-intensive infrastructure initiatives.

These durable products are important, because they are the secret to bamboo’s success.

They include flooring, furniture and ‘flatpack’ housing, as a young designer, who recently won a prestigious architecture prize with his ‘four hour’ bamboo house design, showed.

And in China, bamboo is being used to build storm-drainage pipes, utility poles, street lights, wind turbine blades and shock-resistant exteriors for bullet-train carriages, prompting The Economist to predict last year that China’s bamboo sector is “about to shoot up.”

With a tensile strength greater than that of mild steel, and an ability to withstand compression twice as well as concrete, bamboo products can provide a low- or even negative-carbon alternative to materials like PVC, concrete, plastic and steel.

Replacing traditional materials with bamboo could be an important way to ‘green’ emissions-intensive infrastructure initiatives, and the plant is gaining traction at high levels. At the recent United Nations climate conference in Katowice, Poland, China’s Special Climate Change representative, Xie Zhenhua, said that the plant “can provide valuable opportunities for the green development of developing countries along the Belt and Road.”

And at the high-level Forum on China-Africa Cooperation, held in Beijing this year, all heads of state agreed to an action plan which mentioned the need for “innovative development of bamboo and rattan industries”, citing its potential for poverty alleviation and sustainable economic growth.

At the same time, in Ecuador, bamboo housing has been officially endorsed by the government as a suitable construction material, and was approved for use in the country’s ‘Housing for All’ scheme, which aims to build 325,000 homes by 2021.

If bamboo is such a supergrass, why is it not in use more widely? At INBAR, we recognise a number of obstacles. Lack of information—about the spread of local bamboo resources, and their uses—is a key factor, at the level of both smallholders and policymakers. Speaking at a conference of the UN Convention to Combat Desertification, Paola Agostini of the World Bank summarised the problem: “I am convinced about bamboo, but we still have a way to go to convince many others.”

Cost is another critical issue. As in many nascent industries, a number of products in the bamboo sector are not yet cheap enough to compete with well-established materials. The ‘transition cost’ of swapping resources, and sourcing new suppliers, is an additional barrier.

Strong government support is needed to incentivise the take-up bamboo. The Philippines’ presidential Executive Order, signed in 2010, makes a good start, by “direct[ing] the use of bamboo for at least 25 per cent of public school desk and other furniture requirements.”

The benefits of such support can be seen in China, where strategic subsidies since the 1980s —nd a keen desire by some businesses to stop relying on timber imports—has created an industry valued at $30 billion.

You just saw it more frequently. We didn’t know much about bamboo.”

Her company used wood to make shipping floor containers for all of its products, but the requirements and increasing costs of importing from abroad prompted Yu and her team to explore other options.

Now, the company is making 4 million containers’ worth of bamboo shipping container flooring a year, all of which is locally sourced, and much of which is eventually bought by the shipping behemoth Maersk. “These days, in China we see that bamboo can make so many things. It exceeds expectations. It’s just changed our lives.”

The role of bamboo construction has never been more important. Approximately 70 per cent of global greenhouse gas emissions come from infrastructure construction and operations such as power plants, buildings, and transport. Future development risks locking the world into a high-carbon pathway for hundreds of years.

Hans Friederich is director general of the International Bamboo and Rattan Organisation in Beijing, China.