GST : The way ahead

- जुलाई 7, 2022

- 0

The goods and services tax (GST) is once again fueling impassioned debate, this time stoked by a controversial Supreme Court ruling, Questioning the very idea of the GST. That’s understandable since the tax has generally generated less revenue- and much more discord between the Centre and states than anyone expected. But the GST is beginning to fulfill its potential as a buoyant revenue source. And there are ways to reduce Centre- state friction.

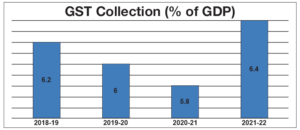

Let us start by considering the data. The chart shows GST collection for the first few years from (2018-19 to 2021-22), seemed to perform poorly, with collections steadily shrinking as a share of GDP. But in 2021-22, there was an impressive rebound, with revenues improving by 0.6 percentage points to 6.4 per cent of GDP.

It could be a sign that the GST is finally coming of age. The first point to note is that 2018-19, 2019-20 and 2020-21 were years of weak economic growth and possibly also years when the GST tax base shrank as a share of GDP, because much of the economy’s growth was in agriculture, which is not subject to the tax. So, the lackluster performance of the GST in these years may have been due to cyclical factors.

Second, there have been substantial reductions in rates. The Reserve Bank of India has estimated that the effective GST rate has been reduced by 2-3 percentage points, which have reduced collections by at least 1 percent point of GDP. Put differently, had rates not been cut, the GST/GDP ratio could be well over 7.5 per cent today.’

Why has the underlying revenue (excluding the rates cuts) improved so sharply in 2021-22 ? Mainly, because the government and the states have been improving GST administration. GST invoices must now be posted before input tax credits are given, firms must fill e-way bills, and more firms are joining the system.

In addition, a hitherto unrecognized factor seems to be playing a major role. A structural change done in the way of indirect taxes. Previously, central excises were collected on imports as countervailing duties. But the VAT levied by states on imported goods was collected only when the goods were sold to consumers. Now central and state GST on imports are collected as Integrated GST as soon as goods cross the international border. In effect, the GST has become a “with- holding tax” at the border. This withholding tax might have increased collections.

For all these reasons, it seems likely that GST collections will remain buoyant, provided that further rate reductions are avoided. And this in turn will generate the revenues needed to smooth relations between the Centre and the states.

GST collections under-performed because of a weak economy and irresponsible tax cuts in which the Centre and the states were both complicit. This combination of high-handedness and weak collections led to a rising chorus of complaints by the states.

Over time, these grievances have morphed into a broader critique, namely that the GST was foisted on the states at the cost of a severe loss of fiscal sovereignty. The passage of the GST reflected one of those rare examples in recent Indian history of bipartisan political consensus on a major policy reform. All the constitutional amendments were passed without a single opposing vote. And all states agreed to the governance and decision- making structure in the GST Council.

The truthful part of the critique is that the GST was implemented by giving up or pooling fiscal sovereignty. But all states were fully aware of the trade- off: Some sovereignty was exchanged in return for efficiency gains and more buoyant revenues. And as the Supreme Court pointed out, state legislatures still retain some ultimate constitutional authority on GST tax policy.

The question now is how the states will use this power. The Supreme Court stated that “the states can use various forms of contestation if they disagree with the decision of the Centre”.

The spirit of co-operative federalism that led to the creation of the GST needs to be revived. The centre should make the first move by displaying nobility, in one of possibly two ways.

The Centre could use the additional GST collections in the compensation pool to ensure that all states receive the full amounts promised for the five-year period from 2016-17 to 2021-22, based on the guaranteed 14 per cent GST revenue growth.

Alternatively, the Centre could extend compensation for another few years. In either case, the new agreement should commit the Centre and states to work together in the GST Council to simplify and rationalize rates – and, in some cases, raise them as originally envisaged as economic conditions improve. This would provide more revenue to all parties. And bringing petroleum into the GST should not be pursued as that would further erode the fiscal sovereignty of the states.

Courtesy from the Centre, more accurate talks by the states, collective action by the Centre and the states, and judicious self-restraint from the judiciary could be a good recipe going forward to restore the GST to its proper and important role.

जीएसटी: आगे की राह

इस बार सुप्रीम कोर्ट के एक विवादास्पद फैसले से प्रभावित हो कर वस्तु एवं सेवा कर (जीएसटी) ने एक बार फिर जोशीले बहस को हवा दे दी है। जीएसटी के मूल विचार पर ही सवाल उठ रहा है। यह समझ में आता है क्योंकि कर ने आम तौर पर कम राजस्व उत्पन्न किया है- और केंद्र और राज्यों के बीच किसी की अपेक्षा से कहीं अधिक विवाद हुए है। लेकिन जीएसटी एक शानदार राजस्व स्रोत के रूप में अपनी क्षमता पर खरा उतरना शुरू कर रहा है। और केंद्र-राज्य विवादों को कम करने के कई तरीके हैं।

जरा डेटा पर विचार करके शुरू करें। चार्ट के अनुसार पहले कुछ वर्षों (2018-19 से 2020-21 तक) का जीएसटी संग्रह सकल घरेलु उत्पाद के अनुपात में खराब प्रदर्शन करते हुए लगातार घट रहा था। लेकिन 2021-22 में, एक प्रभावशाली पलटाव हुआ, जिसमें राजस्व 0.6 प्रतिशत अंक बढ़कर सकल घरेलू उत्पाद का 6.4 प्रतिशत हो गया।

यह एक संकेत हो सकता है कि जीएसटी आखिरकार परिपक्व हो रहा है। ध्यान देने वाली पहली बात यह है कि 2018-19 के विपरीत, 2019-20 और 2020-21 कमजोर आर्थिक विकास के वर्ष थे और संभवतः ऐसे वर्ष भी थे जब जीएसटी कर आधार जीडीपी के हिस्से के रूप में सिकुड़ गया था, क्योंकि अर्थव्यवस्था का अधिकांश विकास कृषि में था, जो कर के अधीन नहीं है। इसलिए, इन वर्षों में जीएसटी का कमजोर प्रदर्शन चक्रीय कारकों के कारण हो सकता है।

दूसरा, दरों में भारी कमी की गई थी। भारतीय रिजर्व बैंक ने अनुमान लगाया है कि प्रभावी जीएसटी दर में 2-3 प्रतिशत अंक की कमी की गई थी, जिससे संग्रह में जीडीपी के कम से कम 1 प्रतिशत अंक की कमी हो हुई होगी। दूसरे शब्दों में कहें तो अगर दरों में कटौती नहीं की गई होती तो आज जीएसटी/जीडीपी अनुपात 7.5 फीसदी से अधिक हो सकता था।

अंतर्निहित राजस्व (दरों में कटौती को छोड़कर) में इतनी तेजी से 2020-21 में सुधार क्यों हुआ है? मुख्य रूप से, क्योंकि सरकार और राज्य जीएसटी प्रशासन में सुधार कर रहे हैं। जीएसटी चालान अब इनपुट टैक्स क्रेडिट दिए जाने से पहले पोस्ट किए जाने चाहिए, फर्मों को ई-वे बिल ऑनलाइन भरना होगा, और अधिक से अधिक कंपनियां सिस्टम में शामिल हो रही हैं।

इसके अलावा, अब तक एक अपरिचित कारक एक अहम भूमिका निभा रहा है। अप्रत्यक्ष करों के संचालन के तरीके में एक संरचनात्मक परिवर्तन किया गया। पहले, केंद्रीय उत्पाद शुल्क आयात पर प्रतिसंतुलन शुल्क के रूप में वसूल किया जाता था। लेकिन राज्यों द्वारा आयातित वस्तुओं पर लगाया जाने वाला वैट तभी वसूला जाता था जब माल उपभोक्ताओं को बेचा जाता था। अब आयात पर केंद्रीय और राज्य जीएसटी को एकीकृत जीएसटी के रूप में जैसे ही माल अंतरराष्ट्रीय सीमा पार करता है एकत्र कर लिया जाता है। असल में, जीएसटी सीमा पर ‘विदहोल्डिंग टैक्स’ बन गया है। इस विदहोल्डिंग टैक्स से कलेक्शन में बढ़ोतरी हो रही है।

इन सभी कारणों से, ऐसा लगता है कि जीएसटी संग्रह में तेजी बनी रहेगी, बशर्ते कि दरों में और कटौती से बचा जाए। और यह बदले में केंद्र और राज्यों के बीच संबंधों को सुचारू बनाने के लिए आवश्यक राजस्व उत्पन्न करेगा।

कमजोर अर्थव्यवस्था और गैर-जिम्मेदार कर कटौती, जिसमें केंद्र और राज्य दोनों की मिलीभगत थी, के कारण जीएसटी संग्रह का प्रदर्शन कम रहा। मनमानी और कमजोर संग्रह के इस संयोजन ने राज्यों द्वारा शिकायतों की भीड़ बढ़ाई।

समय के साथ, इन शिकायतों को एक व्यापक आलोचना में बदल दिया गया कि राजकोषीय संप्रभुता के गंभीर नुकसान की कीमत पर राज्यों पर जीएसटी लगाया गया था। जीएसटी का पारित होना बहुदलीय राजनीतिक सहमति के हाल के भारतीय इतिहास में उन दुर्लभ उदाहरणों में से एक प्रमुख नीति सुधार को दर्शाता है। सभी संवैधानिक संशोधनों को एक भी विरोधी मत के बिना पारित कर दिया गया। और सभी राज्य जीएसटी परिषद में शासन और निर्णय लेने की संरचना से सहमत भी हुए।

आलोचना का सच यह है कि जीएसटी में राजकोषीय संप्रभुता को छोड़ना या समाहित करना शामिल था। और सभी राज्य व्यापार-बंद के बारे में पूरी तरह से अवगत थे: दक्षता लाभ और अधिक राजस्व के बदले में कुछ संप्रभुता का आदान-प्रदान किया गया था। और जैसा कि सुप्रीम कोर्ट ने बताया, राज्य विधायिका अभी भी जीएसटी कर नीति पर कुछ अंतिम संवैधानिक अधिकार बरकरार रखती है।

अब सवाल यह है कि राज्य इस शक्ति का उपयोग कैसे करेंगे। सुप्रीम कोर्ट ने कहा कि ष्राज्य केंद्र के फैसले से असहमत होने पर विभिन्न प्रकार से प्रतिवाद कर सकते हैं।

सहकारी संघवाद की भावना जिसके कारण जीएसटी का निर्माण हुआ, को पुनर्जीवित करने की आवश्यकता है। केंद्र को संभवतः दो तरीकों में से एक में उदारता प्रदर्शित करते हुए पहल करना चाहिए।

एक केंद्र साझा मुआवजा में अतिरिक्त जीएसटी संग्रह का उपयोग करते हुए सभी राज्यों को 14 प्रतिशत जीएसटी राजस्व वृद्धि की गारंटी के आधार पर 2016-17 से 2021-22 तक पांच साल की अवधि के लिए वादा की गई पूरी राशि दे दे।

वैकल्पिक रूप से, केंद्र मुआवजे को कुछ और वर्षों के लिए बढ़ा सकता है। किसी भी मामले में, नए समझौते को केंद्र और राज्यों को जीएसटी परिषद में दरों को सरल और तर्कसंगत बनाने के लिए मिलकर काम करने के लिए प्रतिबद्ध होना पड़ेगा – और, कुछ मामलों में, उन्हें मूल रूप से परिकल्पित किया जाना चाहिए क्योंकि इससे आर्थिक स्थिति में सुधार होता है। इससे सभी पक्षों को अधिक राजस्व प्राप्त होगा। और पेट्रोलियम को जीएसटी में लाने के विचार को आगे नहीं बढ़ाया जाना चाहिए क्योंकि इससे राज्यों की राजकोषीय संप्रभुता और कम हो जाएगी।

केंद्र से उदारता और राज्यों द्वारा अधिक सटीक वार्तालाप, केंद्र और राज्यों द्वारा सामूहिक कार्रवाई, और न्यायपालिका से विवेकपूर्ण आत्म-संयम जीएसटी को उसकी उचित और महत्वपूर्ण भूमिका को बहाल करने के लिए एक अच्छा नुस्खा हो सकता है।